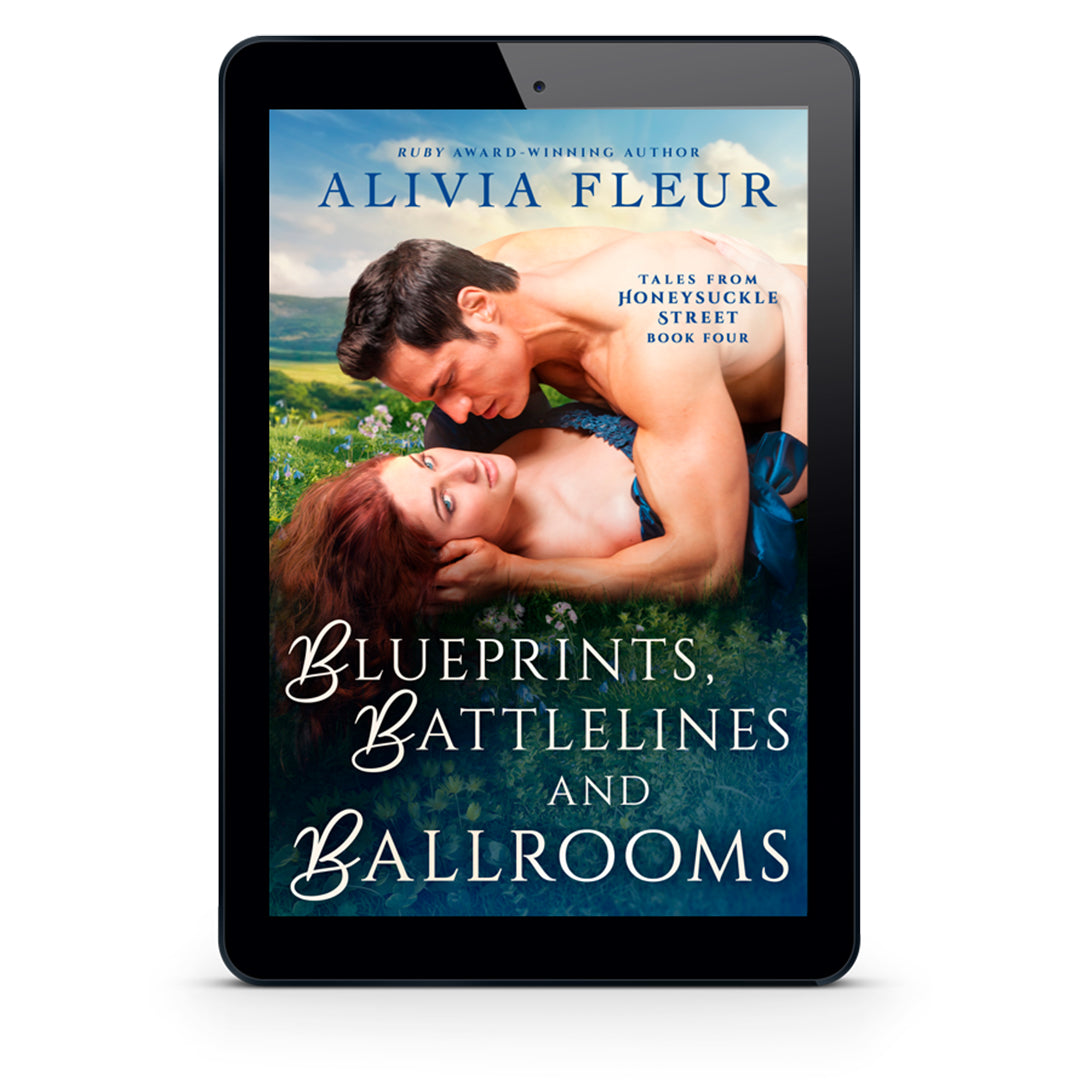

Blueprints, Battlelines and Ballrooms

Blueprints, Battlelines and Ballrooms

Book 4 in the Tales from Honeysuckle Street series

A workplace historical romance

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Couldn't load pickup availability

- Purchase the eBook instantly

- Receive download link from BookFunnel via Email

- Send to preferred E-Reader and start reading!

PAPERBACKS

- Purchase Paperback

- Receive confirmation of order

- Paperbacks are printed on demand and shipped in 5-10 business days

SYNOPSIS

SYNOPSIS

Johannes Hempel is a man enthralled by the past. Happiest with a pencil behind his ear and a chisel in hand, he longs to craft homes that recall a lost age, even as the world around him demands speed, progress and conformity. After months of searching, he secures a position with an architectural firm, but there’s one complication—he is constantly distracted by the principal architect’s captivating daughter.

Florence Murray didn’t traverse half the globe to go slow—this is her time, and she intends to grasp it. London is miles away from the parochialism of Australia and here, she will prove herself. She’s a woman of ambition, intelligence and boundless determination who is tired of the old-world attitudes that refuse to give her a place at the drafting table. She will not be distracted by her father’s old-fashioned—yet adorably quiet, and exceptionally strong—assistant.

She will not allow her heart to be broken again.

When Johannes and Florence are tasked with completing an important project together, old world values and modern ambitions collide. Florence’s daring ideas and racing mind exasperate Johannes, who prefers a steady, methodical approach. Yet in the friction between them, sparks fly.

Alone, the world sees them as weak.

But together, can they build something enduring?

Something that might last…

Forever?

Chapter One Look Inside

Chapter One Look Inside

Chapter One

17 January 1877

Some said the cold helped.

Some said only heat.

Some claimed cod liver oil miraculous.

Some said to avoid temperamental foods. Others said only eat food with spice, food without spice, food that stayed heavy in the stomach, or food with no weight at all.

Don’t move too much.

Don’t stop moving.

But on days like today—when her shoulder ached, her back stayed stuck, and with red raging pain coursing through her—Florence was sure the only thing that would release her from her pain was death.

‘How long has she been bedridden?’

Florence pushed her awareness through the languid, laudanum-induced fog. That was a new voice. A voice she had never heard before. Which meant little here in London where every voice, except for her parents’ familiar tones, was new. A male voice. Stern, with hard edges.

The side of the bed dipped. The back of a hand brushed her forehead. Cool. Efficient.

A doctor.

Another wretched doctor.

‘Mrs Murray? Where is the pain at its worst?’

Florence hesitated, then forced her eyes open. A small part of her flinched with the fear that any inconsequential movement might cause more pain. The room, still grey with early morning, glistened, then settled. Everything was warm, too warm for this country, where the cold had become her fast companion since that first day they had stepped off the boat and into a snow-speckled city. Heavy coal smoke infused the air in her next breath. The stove pulsed molten orange in the corner. A stove lit in a bedroom was not a good sign. Only the very rich or the deathly ill warranted the expense of a fire lit in their bedrooms. And they were certainly not the former.

‘Mrs Murray? Can I turn you?’

Florence shook her head. ‘I’ve seen too many doctors. They never help.’

He chuckled. ‘Trust must be earned with you. That is not a bad thing. Doctoring is a noble profession, but not every practitioner is of noble intention. Speak with me, then. Tell me about the pain.’

Florence let her lids droop without closing them so she could study him through an imperious line. Once, she would have lain here demurely and tried to be a pleasant patient, but that Florence had lived a long time and too many remedies ago. What type of man had her parents brought in now? Somewhere between her and her parents in age, a little grey in his hair, a clean black suit… He rested weathered hands on his knees and folded his fingers into his palm. A wedding band glinted in the light. Was an English doctor better than an Australian one? He smelt better. That was a place to begin.

‘You wash your coat,’ she said.

He huffed, but did not smile. ‘I was a young assistant in Crimea. I do not hold to old traditions, and I certainly do not believe the blood and pus of past patients stuck to my coat is a help to future ones.’

A watch chain stretched across his waistcoat. She waited for him to consult the timepiece hidden in his pocket, but he didn’t. He just waited.

Telling him a story wouldn’t do any harm.

Maybe.

‘I was thrown from a horse and landed badly. Some years ago. When I was not a girl but not grown either.’ Florence rolled onto her side, away from him and the room, so that she faced the wall. A rustle of skirts, and her mother’s small, familiar hands loosened her chemise and exposed her back. ‘I’ve never been right since. The pain is almost constant.’

‘You could have broken your neck. Would that have been better?’ the doctor asked.

‘Some days, I think so.’ She spat her words at the wall. ‘Because then I would not have had to suffer at the hands of your profession.’

Perhaps she spoke with more venom than he deserved. After all, he lived here, three months of rolling sea and skies away from the place where a countryside bone setter had wrestled her body into some semblance of a normal shape. If they had stayed put, maybe she would have healed. But her father had loaded her into a sulky to return to the city. There, she had been sliced and poked by doctors who had made their diagnosis over why she wouldn’t heal, then put her back together with wire and splints.

‘She broke her shoulder, her knee, and her leg when she fell.’ Her father. ‘We were some miles from the city, and a local man did his best. By the time we returned to town, she had started to heal wrong, and an infection had set in. The city doctors tried to fix her—’

‘They re-broke my shoulder,’ she whispered to the wall, and the pain bit almost as bad as it had back then. ‘Pinned my leg, used splints and plaster casts. But the pain stayed inside me, in all of me, even in the unbroken parts. They let my blood because they thought it might be bad, but it made no difference. And when my husband died, they told me the pain was my grief, and that it was my own fault I wouldn’t heal because I would not let him go.’ Florence hunched over as much as she could, to the point where the stiffness started, and kept her focus on the peeling edges of the faded pink wallpaper. If she closed her eyes, she’d see the memory, so she kept them trained on the wall. That way, she did not have to look at her parents or at this new medical man they had brought to inflict his knowledge on her.

The doctor walked his fingers over her skin, his pressure firm and needling. Florence flinched when he pushed too hard.

‘They used wire?’

A long pause, just long enough for a nod.

‘And the doctor had been trained?’

Had the doctor been sober? That might have been the better question.

‘The apothecary thought rheumatoid might have set in,’ her mother said. ‘He recommended these.’

One of them—probably the doctor, for there was no tenderness in the touch—pulled her chemise across her back and tugged the blanket up again. He moved roughly, but that was a comfort in itself. Many a doctor or their assistants chose an overly tender bedside manner.

Florence gritted her teeth as she sank to the side. She could stay here, stare at the wall, and let the three of them try to resolve the problem that was her.

Damn that thought to blazes.

Flattening her palm against the wall, she heaved herself onto her back and, with an almighty effort, onto her opposite side so that she could watch them all from her horizontal vantage point.

The doctor was holding her pills at arm’s length. He set the glass bottle back on her dresser, then tapped the lid.

‘Don’t take any more of these. Mercury will not help you. It may be making things worse.’ He picked up another bottle and shook his head. ‘Or these. I would like to look at your blood. Not let it,’ he said with a knowing smirk as she shied. ‘Just a small vial. We can tell from your blood if there is rheumatoid. I don’t think so, but at least we will know. Coming off the pills will not be easy.’ He addressed this last sentence to her parents. ‘If she cannot sleep, give her a little laudanum, but not too much. No point in treating the pain if she develops an addiction.’

Her parents muttered and mumbled something obsequious as the doctor tucked his coat over his arm and collected his bag. His enthusiasm was not pure self-aggrandisement, but it wasn’t free from it either. He tugged his hat with that common air they all shared—the mark of a man who paid respect but, deep down, considered himself superior.

‘Are you going to cure me, doctor?’ She pushed herself up a little, even though the movement made the pain grind like stone on stone. ‘I demand your honesty. My parents delight in deception, but I am tired of it.’

‘A cure? Not with pills or exercises. There are theories on surgery and antiseptic, and new procedures all the time. The only way is to operate to repair the damage. I have a friend, incredibly talented. He offers consults to many fine families. If I speak with him, I think he will be interested in your case. He likes a challenge. But surgery with a private physician comes with a fee.’ He scrawled something on a note, tore it from his book, and passed it to her father.

Florence closed her eyes against her father’s pathetic frown as her mother covered her mouth with a little oh. She sank into the pillow and used her good hand to pull the quilt a little higher, covering her head so she did not have to hear their stilted goodbyes.

He genuinely believed he had the solution that would grant her a better life, but it was all the same. Underneath his words lay the same diagnosis she’d been given since she’d first crunched into the dirt and the townsfolk had bent over her anguished, contorted body.

Broken. She was broken.